The $15trn question: who will pay for tomorrow’s infrastructure?

With fiscal constraints a dominant feature of the economic landscape across major economies, politicians’ eyes are increasingly alighting on the trillions managed by financial institutions. They are knocking on the doors of banks, pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds and asset managers in a drive to persuade them that investing in a wide range of infrastructure projects would be good for their balance sheets, their investors and their policyholders.

The sums are huge. McKinsey & Company has estimated that globally an average of $3.7trn of infrastructure investment will be needed every year just to keep pace with economic growth. A large slice of this will be financed by governments, but this will only go so far, according to the Global Infrastructure Hub, a G20 initiative supported by the World Bank. In a recent report it estimated that by 2040 the world faces an investment gap of $15trn. However you look at the challenge, the sums needed from the private sector to address it are huge.

Institutional money is there and is constantly seeking the most appropriate assets to invest in, but the willingness to commit it to massive public infrastructure projects is very restrained, according to Manpreet Kaur Juneja, an infrastructure specialist with the World Bank: “Despite their ample resources, private financiers often view infrastructure investments as high risk. These perceived risks are the result of a complex set of issues, such as large asset sizes, long project life cycles, complex structuring, large initial irrecoverable costs, political and regulatory changes, wariness of citizens to accept privately run services due to perception of higher prices, and the lack of tradability of infrastructure assets,” she said in a recent World Bank blog.

The shopping list of projects debt-constrained governments are seeking injections of vast amounts of private sector finance for gets longer every time a finance minister is forced to answer the question: how are you going to pay for that?

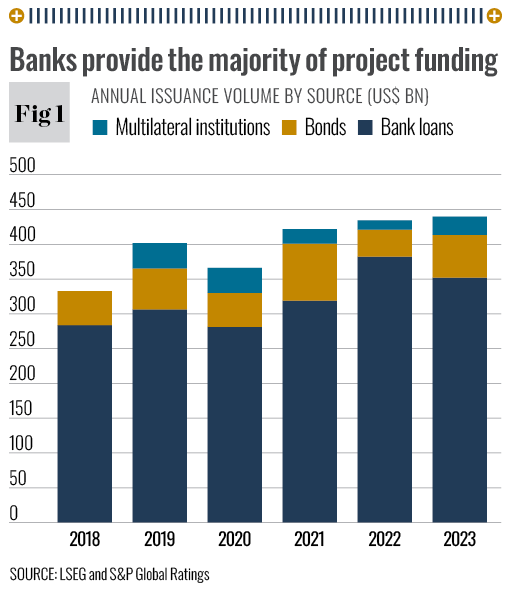

Many of the projects seeking private sector finance have been talked about for several years and some have already found a place in investment portfolios, either through direct participation or through one of the many infrastructure bond offerings (see Fig 1). So, what do these projects look like and why might they appeal to private investors?

Financing forum

When some of the world’s biggest investors gather in Los Angeles in September for McKinsey’s 10th Global Infrastructure Summit, they will be tackling a broad, ambitious agenda that embraces a wide range of opportunities:

>Delivering smart, green infrastructure: The energy and digital transitions require a huge portfolio of new assets, from chip plants to offshore wind farms and modern port terminals.

>Renewing critical infrastructure assets: While there is significant demand for construction of new projects, most of the world’s infrastructure already exists. Much of this brownfield infrastructure requires rejuvenation to become more technology-enabled and energy-efficient.

>Integrating AI and disruptive technologies: An enduring industry challenge given long asset lifecycles, technology fragmentation, and other hurdles from privacy concerns to skill gaps.

>Embracing the age of digital infrastructure: Data centres, fibre networks and semiconductor fabrication facilities will all become critical assets for investors and governments.

Transforming this shopping list into attractive investment opportunities will run into the harsh realities of geopolitical uncertainty and financial volatility, reinforcing the long-standing reluctance of potential investors.

As the world emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a burst of enthusiasm for stimulating the urgently needed economic recovery through infrastructure projects. This was typified by President Biden’s Green New Deal, with its echoes of his predecessor Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal that revived the US economy so successfully in the 1930s. Biden wrapped up a range of green transport projects, such as encouraging a switch to electric vehicles and the development of sustainable aviation fuels, along with major investments into renewable energy, grid modernisation, carbon capture and adaptations to meet the challenges of climate change. These plans were launched through the Inflation Reduction Act 2022 and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act 2021. These committed hundreds of billions of dollars in public funding but also touted the prospect of raising $250bn from the private sector. This process had barely started when Donald Trump entered the White House at the beginning of the year, quickly making it clear that the Green New Deal was dead and that the flow of public money into hundreds of projects underway or ready for launch could be about to dry up.

The winds of change

Inevitably, investment portfolios are being rebalanced in response to these shifting policy priorities, further complicated by the continuing shock waves from the Trump administration’s unpredictable tariff policies. It is no surprise given the shunning of net zero ambitions and the reversal of policies for reducing the use of fossil fuels that renewable energy projects, in particular, are struggling to raise finance. Some renewable-focused funds have seen reduced inflows, while traditional infrastructure assets – such as roads, bridges and airports – are regaining prominence.

This does not mean that the flow of money into renewable energy projects will dry up, says Illia Kyslytskyi, asset manager at Florida-based Yaru Investments: “The threat of the downfall of the Biden administration’s Green Deal initiatives has consequences for green infrastructure investment in America’s future. Whereas certain initiatives would be denied federal support, state governments and the private sector may still drive investment into wind and solar power, electric vehicle charging stations, and climate adaptation programmes.”

Investors will still be looking for some reassurances, however: “As far as such programmes go and whether they continue to gain institutional investors, that hinges on regulatory guarantees, tax credits, and the development of new funding vehicles.”

These shifting priorities are not unique to the US. In the UK and Europe, the need to ramp up defence spending has led to a reappraisal of government spending priorities. In some countries – Germany being the most obvious example – it has also led to long-standing fiscal and debt rules being reassessed. Such major policy shifts have consequences across other asset classes.

Germany’s shift from its historic reluctance to borrow to a ‘whatever it takes’ plan for military and infrastructure spending helped boost 10-year Bund yields to nearly three percent in March, a two-year high. This has driven up bond yields across the Eurozone, thanks to German debt’s role as the de facto benchmark for the bloc’s market.

This has led to warnings that the additional borrowing costs countries might incur relative to Germany could widen, making it much harder for some countries to borrow to support increased military expenditure. Cue yet more eyes being cast towards the private sector, along with new solutions coming on stream. It has given a fresh impetus to the development of blended finance solutions – vehicles for bringing together private and public finance in a way that delivers for both sides. These are nothing new.

A private accord

In the UK in the mid-1990s and into the current century, the Private Finance Initiative played a major role in UK infrastructure development, building many new schools and hospitals. This served its purpose at the time but needs a rethink, said investment specialist HICL Infrastructure in a recent report published by Investors Chronicle: “There is now a pressing need for a new public-private co-operation model. One that retains successful elements of past initiatives, while learning from their shortcomings. This evolved model should be less cumbersome, allowing private capital to engage more dynamically with public projects.”

Green Bonds offer viable model

The International Finance Corporation, part of the World Bank, has led the creation of a viable green bond offering. The aim is simple: to finance sustainable, climate-smart projects with a positive environmental impact, with the goal to speed the transition to a low-carbon economy. IFC green bonds were first issued in 2008 as senior unsecured debt, following that in 2013 with the first global US Dollar benchmark green bond in the market, which took green bonds from being niche products to mainstream assets.

Other multi-national institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank, have also helped grow the market. The IFC’s green bond programme is now complimented by a similar social bond programme with broader objectives, including affordable housing, access to healthcare and education, food security and clean water projects. It is estimated that by mid-2024 the global green bond market surpassed $2trn in cumulative issuance since inception, with over $500bn issued in 2023. For social bonds the cumulative issuance is now over $800bn.

The Labour government in the UK is making plenty of noise about the need for infrastructure investment, giving the green light to projects such as the Lower Thames Crossing and unleashing a series of reforms to the planning system to make it easier for major housing and industrial developments to be approved. It will have to move quickly if it wants to attract large sums of highly mobile international capital.

Across Europe, everyone is in the same position. France, Germany and the Nordics are already leveraging new models of public-private partnerships (PPP) to drive infrastructure expansion. The European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Facility is also playing a critical role by providing grants and loans for strategic infrastructure projects, providing that secure foundation of public financing private investors are looking for.

Europe, faced with the urgent need to boost its defence spending in the face of America’s equivocal attitude to maintaining its long-term commitment to European security, is also exploring the integration of infrastructure development with defence needs. Dual-use infrastructure, such as ports, railways, and cyber networks, already serve both economic and security purposes. This blending of infrastructure and defence spending is in its early days but is an attempt to address the fears of some that defence spending may crowd out infrastructure funding.

Canada has long been regarded as a PPP leader using an availability payment structure, where the government pays the private operator fixed periodic fees in return for delivering and operating the infrastructure to agreed service levels. Because the government assumes usage risk in this model, private partners enjoy a secure revenue stream as long as they meet performance standards.

According to the Inter-American Development Bank, many Latin American countries have successfully embraced PPPs to close infrastructure gaps. It says the region leads the developing world in attracting private participation in infrastructure, with an estimated $770bn of private investment pulled in over the last 30 years – roughly 25 percent more than East Asia and Pacific countries in the same period.

Tax incentives are an obvious route and have been used widely in several major economies

These PPP models mitigate some of the risk involved in infrastructure investments, but they have not been sufficient to close that huge gap. More needs to be done. The projects are there, governments are almost pleading for private sector investment, so what more is now needed to unlock those funds?

Some of the reluctance of the decision-makers controlling major investment funds to commit to large-scale investment in infrastructure has been the lack of liquidity. The long-term commitments implicit in major infrastructure projects often means the assets are locked into a portfolio, even when the promised returns do not materialise. This especially inhibits direct investment in major infrastructure projects, unless other incentives offset the liquidity concerns.

Illiquid courage

Investment via bonds provides some protection against this, but often there is no ready-made market so exit options can be very limited. Kyslytskyi says the illiquidity challenge is a significant barrier but solutions are at hand: “Liquidity remains a fundamental concern in infrastructure investment, as such assets are illiquid and long-term in nature. Investors are circumventing this issue by increasing their participation in secondary market transactions, where infrastructure stakes are traded to manage portfolio flexibility. Infrastructure debt instruments, such as project bonds and infrastructure debt funds, offer access to the asset class with greater liquidity than direct equity investment. Other investors are also matching listed infrastructure equities with private ownership of infrastructure as a means of balancing liquidity needs.”

Infrastructure bonds are not new but have been a relatively neglected asset class. The renewed pressure to attract private sector funds has led to an expansion in volume and variety, especially with the emergence of a new generation of Green Bonds designed to attract pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds.

These bonds are usually long-duration and inflation-linked, offering predictable, stable returns aligned with the needs of long-term investors such as pension funds. Those features need to be overlaid with government-backed guarantees or co-investment structures to reduce risk, which takes many forms with large-scale projects. The most obvious risk is abrupt changes in government policies, a fear rekindled by the gyrations in US government policy following the change in administration. Another key fear that is never far from the surface in conversations about infrastructure investment is deliverability.

Complex fragility

This was highlighted in a recent report from the Boston Consulting Group which explored the UK’s infrastructure challenge: “Announcing new projects is the easy part. Based on historical data from 2010 to 2015 we estimate that 16 percent of announced projects did not, in the end, proceed, while a further 21 percent have become stuck in the pre-construction period for over a decade.”

Infrastructure bonds are not new but have been a relatively neglected asset class

One of the key challenges – by no means unique to the UK – is the supply chain. With the global demand for materials, skills and expertise ramping up at the same time this could impose a major constraint. The Covid-19 pandemic, geopolitical uncertainties and the blocking of the Suez Canal by just one huge container ship, the Ever Given, for six days in March 2021, reminded everyone of the fragility of complex supply chains.

Fund managers will expect solutions, says Boston Consulting: “In the face of such huge demand, it is not surprising that supply chains might be unable to respond effectively. Based on a series of industry case studies we have identified five common challenges in UK supply chains which underpin this,” providing a tough list for investment managers to address before committing their funds:

1) Scarcity of key inputs across both skills and key components.

2) Lack of co-ordination and leadership at national level and within supply chains. There is no clear pipeline or prioritisation at national level and too little leadership within very fragmented supply chains.

3) The move to a seller’s market: suppliers increasingly face the choice of which clients and countries they work with.

4) Poorly scoped projects: at national and project level there has often not been proper scope optimisation.

5) Lack of effective and integrated commercial strategy.

The UK’s National Audit Office also highlighted the need for greater commercial awareness in a report – Lessons for public infrastructure investment using private finance – published at the end of March: “The government should adopt a commercial strategy to deliver successful outcomes. To achieve this, commercial expertise is needed to undertake an efficient procurement process, supplier contracts must be managed effectively, and contingency plans should include protections and alternative options to mitigate supplier risks.”

While reassurance on these key issues and the development of a more sophisticated infrastructure bond market – with its own robust indices and greater liquidity – will go some way to stimulate the flow of private money, it will have to be matched with some serious incentives.

Tax incentives are an obvious route and have been used widely in several major economies, including the US, India and Brazil, where a new law in 2024 exempts foreign investors from the 15 percent withholding tax on interest from infrastructure bonds issued abroad. Promising stable revenue streams from investments is another tool governments can use, although this comes with political risks as it raises important questions about pricing, access, and equity. As more projects move to user-pay models, such as with the mammoth Lower Thames Crossing project east of London, there is a risk of public backlash, especially if service quality does not match increased costs.

Many institutions also point to the very restrictive treatment of infrastructure assets – mainly because of their illiquidity and valuation challenges – by regulators. This has particularly applied to the European Union and the UK, where tough solvency rules have proved a heavy disincentive. Both the EU and UK regulators are looking at reducing the capital charges levied against infrastructure assets. This has been a prominent theme in the lobbying of the UK’s Prudential Regulation Authority by the sector, aided by pressure from the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves, who has brought leading financial institutions together in a new Infrastructure Taskforce. She has made it clear she expects the private sector to fill the UK’s infrastructure funding gap and has not been shy about taking a more interventionist stance if the incentive route does not produce results.

Liquidity remains a fundamental concern in infrastructure investment

The UK government is already forcing through a major merger of vast local government pension funds in the belief this will make them look more favourably at infrastructure investment opportunities. The UK Treasury is reportedly preparing to formalise an agreement – possibly backed by legislation – that would require pension funds to commit up to 10 percent of assets into private markets, with half of that required to be channelled into UK-based investments.

This has attracted some sharp criticism from advisers who sit at the interface between institutional fund managers and policyholders. “Forcing pension funds to tilt portfolios toward one geography regardless of market conditions could distort asset allocation, reduce diversification, and expose millions of future retirees to lower performance,” warns Nigel Green, CEO of deVere Group, a global independent financial advisory and asset management firm.

“It is not the job of pension managers to carry the weight of industrial policy. If UK firms are being overlooked, there is a reason for it. The solution isn’t to coerce capital into local markets. The solution is to make those markets perform better,” Green says. “People expect their pension contributions to be professionally managed in their best interests and not treated as a national piggy bank,” added Green. It demonstrates just how challenging it is going to be for governments to plug the investment gap. For every solution offered, there is a potential downside, or at least a very careful balancing of competing interests to be worked through.